Ian Fleming was a mediocre writer and a reporter with poor instincts who penned a series of novels which were despised by literary critics, and only become popular because President John F. Kennedy offhandedly mentioned one on a list – we don’t know if he actually liked it – and the phenomenal success of the film series that ensued made Fleming and his estate very rich even though the films have very little to do with Fleming’s writing.

Um, okay.

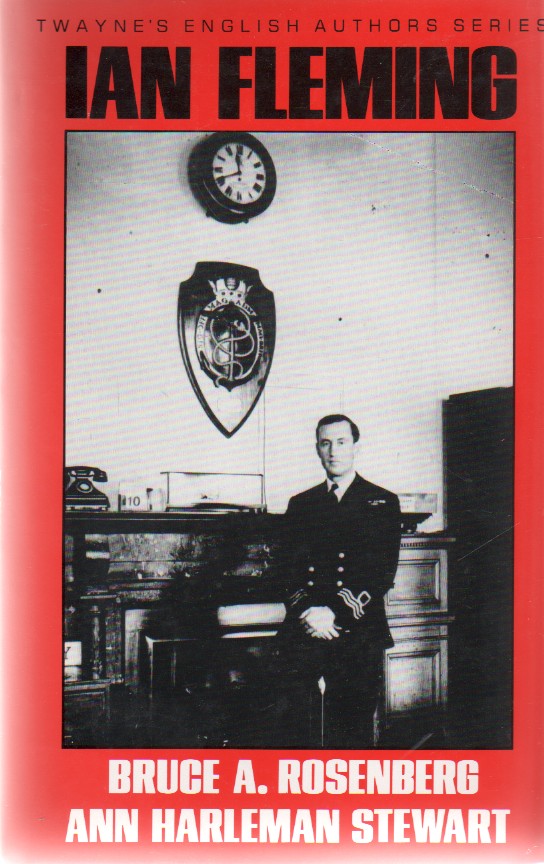

That’s basically the overriding theme of a biography/literary assessment of Ian Fleming by Twayne’s English Authors Series, published in 1989. Other English Authors profiled in this series include Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle, Dick Francis, P.D. James, Barbara Pym, Graham Greene and Daphne du Maurier.

The authors of the Ian Fleming book were a husband and wife team – Bruce A. Rosenberg and Ann H(arleman) Stewart.

The preface to the book begins:

By all the usual standards of belles lettres, Ian Fleming was a mediocre writer. His characters were improbably and often poorly realized. His plots — they have been called “science fictions” — were unrealistic and seldom credible either within individual episodes or throughout the entire economy of the narrative.

Two paragraphs later:

The personality of this fictional secret agent –and not a brilliantly drawn one at that — has impressed itself deeply in our consciousness.

Six paragraphs later:

Ian Fleming, who will never be on anyone’s all-time distinguished authors list,

and

How does a mediocre writer create characters that live on for decades?

With that, the tone for the rest of the book is pretty well established.

This book was written in 1989, a quarter of a century after the death of Ian Fleming. This, the authors claim, allows them to take a more objective look at Fleming and his writing. They say that most of the books about Fleming and his writing were done in the years following his death, when the James Bond craze was at its peak, and that this blinded reviewers to the flaws in Fleming’s writing and indeed, in his life.

Chapters are devoted to Ian Fleming’s life, his time during WWII in Naval Intelligence, his ability as a writer, his inspirations, whether or not the James Bond novels can actually be called “Spy novels”, the women and other characters in the books, the villains (one of the few areas Fleming receives high marks) and an attempt at Fleming’s psychological issues and how the books reflect them.

The authors rely heavily on the analysis contained within Umberto Eco and Oreste Del Buono’s collection of essays contained within Il Caso Bond (The Bond Affair.) Among the essays noted of those of Fausto Antonini (The Psychoanalysis of 007), Furio Colombo (Bond’s Women), Romano Calisi (Myths and History in the Epic of James Bond) and Eco himself (The Narrative Structure in Bond).

The writings of John Pearson, Kingsley Amis and O.F. Snelling are cited, but treated as more lightweight fare. Raymond Benson’s The James Bond Bedside Companion is cited in the bibliography as “Superficial, adoring, but entertaining.”

While the book is scathing in its criticism of Fleming at times, curiously the authors fail on a number of occasions to get their facts correct. On at least two occasions, they mix up events in novels with those that take place in the film version. At one point when discussing how Fleming used Bond as wish-fulfillment they write:

James Bond is portrayed as an expert skier, scuba diver and hang glider, jet and helicopter pilot, high speed racing driver, sky diver, motorcyclist and all-around acrobat; in Fleming’s mature years, golf was the extent of his physical activity.

Fleming never has Bond using a hang glider, nor does he ever pilot a jet or helicopter. I can’t recall sky diving being among his hobbies in the novels, either. He does all of those things in the films.

In a discussion of Goldfinger, the authors cite the film version of events as Fleming’s.

He will irradiate the gold in Fort Knox with a small atomic explosion, thus depriving the American government of its use. In the ensuing financial chaos, he, Goldfinger, will profit financially, while SMERSH gains politically.

In Fleming’s Goldfinger novel, the plot was to actually steal the gold. A small ‘so-called “clean” atomic bomb’ was used to blow the door of the vault, but the goal was then to load the gold onto trains and trucks and steal it.

The final chapter of the book begins as follows:

Few writers in this century has angered their readers as much as Ian Fleming. In general, critics have taken offense at the ethics and morality of James Bond and by extension, of his author. Nearly all of the critiques have been variations of elaborations of the “sex, snobbery and sadism” charge of Paul Johnson (New Statesman, April, 1958). not much has been written about Fleming’s writing skills (or lack of them).

The closing paragraphs describe Fleming as “insecure, limited, exploitative, even despicable” but then a change is made in tone. Sympathy for his upbringing and lack of “emotional nourishment” during that time is cited. Much of the book was spent on Fleming’s flaws, as a person and as a writer, but then talks about how Fleming was able to overcome these by developing “his innate gifts – personal charm, the ability to make friends easily, the ability to write rapidly and clearly.” He was, according to the authors, in his final years able to come to terms with himself and accept his life “as the only possible course he could have taken.”

The book ends:

Out of an enormous pain, he produced more than a dozen books that have brought pleasure to millions of readers.

That isn’t the final sentence I saw coming as I spent the time going through this tome on the life and works of Ian Fleming.

Fleming is a mediocre writer when he is at his most plot-driven, pushing the action along at the expense of characterization. Sometimes his use of summarizing language, to fill in plot gaps or give background information, is absolutely dreadful. I have always felt that Bond has human depths and possibilities that Fleming was too rushed (or too uninterested) to explore. But at his best, such as in descriptions of food or landscapes, Fleming is a remarkably vivid writer. He manages to convey the textures of the material and sensual life more vividly than many “better” literary authors. He is also expert at using apparently minor facts —a brand of cigarettes, say, or a type of suitcase– as telling details that give authenticity to his created world. He may be shallower than, say, Le Carre or Deighton, but he is much more evocative and stimulating linguistically, and he will probably be read still when they have been forgotten.

The Twayne book is despicable, undoubtedly the worst literary study of Fleming ever written.

Rosenberg and Stewart deride Fleming as a mediocre writer (because he overused the word “hiss”!), use pop psychology to suggest he was a repressed homosexual, convict him of antisemitism via guilt-by-association (since Buchan was an antisemite, Fleming must have been since he was influenced by Buchan), and find an excuse to dismiss every interesting part of his books (the nature-of-evil conversation in Casino Royale is bizarrely slagged off as copying Graham Greene). The hack authors also repeat a mistake from “The Bond Affair” and call one of the Spang brothers a hunchback–that, along with the errors you mention, demonstrates the shallowness of Rosenberg and Stewart’s study. Twayne took a giant misstep in selecting critics whose incompetence was only dwarfed by malice.

Thanks for the comment and the additional examples of how ridiculous this book is!

Spot on. It’s tempting from a completist point of view to own this book, but I don’t want it polluting my bookshelf.